Seven Key Principles of Leading Innovation in New Areas

By Scott Bowman

I am in the business of helping leaders of organizations create new value—that’s the job of innovation. As a managing partner at an innovation and strategy consulting firm, I have come to learn that creating new value demands new thinking, which often requires a change in context. Bold new thinking often comes from unexpected places. I experienced that first-hand this year.

A short time ago, I had the privilege of accompanying my father and seven others to South Sudan—the world’s newest country. Less than 10 years ago, my dad’s organization, Partners in Compassionate Care (PCC), founded and built Memorial Christian Hospital just outside of Bor—capital of the Jonglei state, South Sudan’s largest state by population. Since opening, the hospital has treated over 80,000 people and is now staffed entirely by Sudanese. It also has the only X-ray and ultrasound system in this impoverished state. All of this is mind-bending.

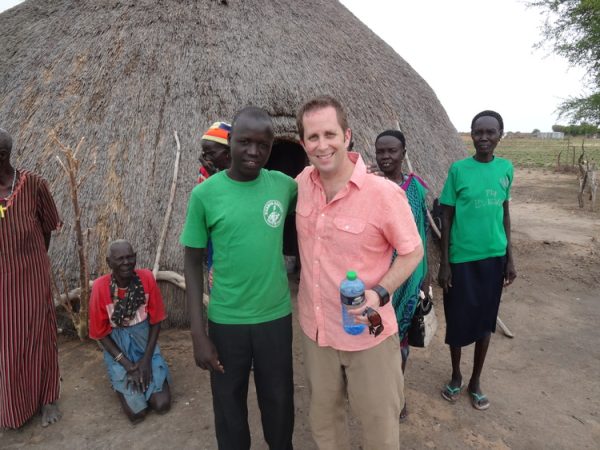

Scott Bowman mentors a Team of entrepreneurs from John Garang University of Science & Technology in South Sudan.

This was my first trip. I’ve been a long-time Advisory Board member and have assisted the organization at key points, but I had never visited the war-torn land. I went there to experience the work, and to engage in meetings with local leaders. I also went there to teach classes in entrepreneurship & new business creation at John Garang Memorial University of Science and Technology and meet with entrepreneurs.

Being in South Sudan, talking with entrepreneurs and meeting with local leaders was a radical change in context. I expected to be moved, to grieve quietly, to return challenged and grateful. I did not expect to gain so many fresh insights. I should have known to expect the unexpected.

The most surprising thing was the unexpected parallels that exist between my family’s work in South Sudan and the work of innovation leaders in large organizations. Reflecting on my family’s experience in South Sudan, I discovered seven key principles of leading innovation in totally new areas—regardless of the context:

Principle 1

Set a bold and compelling aspiration that will motivate others and demand new thinking. At Clareo, I regularly work with senior executives who are exploring, defining and building bold new business innovation, and at times, entirely new businesses. A powerful aspiration is central. Daniel Burnham, Chicago architect and urban planner, famously said, “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood.” Put another way, if it’s clear how you’ll get from where you are today to your long-term vision, you’re not thinking big enough. Modest aspirations lead to incremental thinking; audacious aspirations lead to new and breakthrough thinking. When our team went into Sudan in the mid-2000s, everyone told us to focus on temporary medical clinics, staffed by teams of western practitioners. Instead, and in response to local community feedback, our leadership set a much bolder vision: Establish a surgical hospital, staff it with local African medical teams, and make it self-sustaining. That vision was audacious and required a new level of partnership with community leaders and likeminded NGOs, developing a sustainable revenue model for the hospital rather than merely relying on western funding sources. It also required investing in capability development and infrastructure, including technology. We’re not there yet, but progress to date has been astounding.

Principle 2

The context of change is as vital as the change itself. Often as leaders we focus on the development of strategies and plans to drive innovation, but fail to realize that innovation happens with and through people, and must be accomplished within a given cultural and environmental context. Since achieving independence from the Sudan in July 2011, South Sudanese leaders have been seeking ways to create unity, rally its people around a cause greater than themselves or their intra-tribal differences, and empower their people to build their new nation. And, while the government plays a certain role, it is the community religious leaders who are most influential in moving the hearts of people and motivating change at the local level. By bringing together religious leaders from diverse communities and tribes, PCC has been able to build a more sustainable base of support for its efforts in the country, and in so doing, win the support of county and state government leaders in the process. The pastors and community leaders drove people to get involved to help co-create and build the hospital, and have maintained community involvement at key points. Because of this anchor of support, local government leaders have stepped up and made co-investments, such as the development of an airstrip, donating land, and providing security forces at critical points. None of this would have happened without engaging the right influencers who have the ability to win the hearts and minds of their people and motivate change at a local level. To achieve success, innovation leaders should carefully consider the context of change, as well as the formal and informal networks that are able to influence adoption of new ideas.

The Women & Children’s Ward at MCH Hospital in south Sudan.

Principle 3

Start with their needs, not your ideas, and focus on how to enable them. All too often as innovation leaders, we begin with the solution, when we should begin with the customer, and the problem to be solved. Getting there requires asking the right questions. When PCC began its work, they didn’t begin with the western solution (medical aid, revolving clinics); they began by probing deeply with community leaders to uncover their needs, and to co-create the solution (a surgical hospital with satellite healthcare clinics). Additionally, along the way, PCC has challenged local leaders to take ownership over their hospital—inspiring them to step up and invest, and enabling them with the resources and capabilities needed. In the early years, the community built tukels (housing) on the compound and helped build the wall around the compound. Today, they are the ones coming up with new ways to drive financial sustainability through new revenue models. In the same way, innovation should begin with the customer, with well-articulated and high value problems to be solved.

Principle 4

In the early stages, small, targeted projects can be more effective than “big bang” efforts. This may seem to be at odds with my point about a bold vision, but it’s not. A vision sets the aspiration, strategic frame and boundaries. However, within that frame there is value in starting small and earning the right to do more. Innovation leaders often seek out large, transformational, reputation-forming projects. However, large projects can be difficult to sustain, and often end up abandoned. Smaller projects can generate positive momentum, or wind in the sails, and earn the team the right to do more. PCC took this approach in South Sudan: a small hospital, well staffed, and a model that could be proven out, rather than a large capital-intensive project at the outset. Achieving early success can be a path to momentum in the NGO world andthe corporate world.

Principle 5

Foster a culture of testing, adaptation and learning. At my firm, Clareo, we apply the principles of design and “Lean Startup” when working on new innovations—especially those that are further out from a company’s core business. We focus on possibilities, not probabilities; and we begin with hypotheses we can test, not business cases we can prove. In South Sudan, tactics on the ground continually change and evolve. Organizations that succeed are the ones that are able to pivot, while staying true to their mission.

“Africa has 30 percent of the world’s natural resources and some of the best climate conditions, rainfall and soil in the world, and an abundance of arable land. And yet 35 percent of Africa’s population is chronically under-nourished and the entire continent contributes just 1.3 percent of the world’s production.”

Principle 6

Maintain a relentless focus on eradicating dependency. The world has created a massive crisis of dependency in Africa. The Western model of huge outside investment, supported largely by expatriate staff, simply does not work over the long run. Local markets are disrupted, creating more harm than good. Large NGOs are incentivized to maintain significant in-country resources and defend their core operations. Nationals are conditioned over time to seek handouts and aid instead of solutions that empower them. PCC’s approach has been precisely the opposite, working with leaders and focusing on empowerment, self-sufficiency and sustainability. Corporate leaders, especially those seeking to innovate within and around an established core business, should take a page from this book. Rather than bringing in large teams from the outside to create the strategy for them, we find it far more effective to involve and empower the leaders responsible for carrying innovation and change efforts forward. Failing to do so results in binders of material doing little more than sitting on the shelves of leaders who sponsored the work, abandoned like failed projects in the developing world.

A patient receives a vaccination at the MCH Clinic in South Sudan.

Principle 7

Accelerate value creation through partnerships with like-minded organizations. Don’t try to go it alone. Pick reliable partners that are motivated to act. PCC made this mistake early on, but thankfully learned this lesson. Innovation is a people-business, and the people you work with must be aligned with your mission and values or the partnership will break down over time. The cost of failure is significant.

As I’ve reflected on these seven principles, I’ve found broad applicability to my corporate clients. I went to South Sudan a teacher, and returned a student.

I am now half a world away from South Sudan, both figuratively and literally. And yet, somehow the lessons I learned there transcend geography, culture, and organizational context. As a practitioner of innovation, I should have known to expect the unexpected. I guess I’m still learning. That, too, is the job of an innovator.

See also: Clareo and Client Partner to Improve Healthcare in South Sudan